Last week at work I wrote a blog post about friendships in literature for National Best Friends Day. (You can read it HERE if you want.)

I had some ideas of books I wanted to highlight but needed a few more, so I did a bit of internet research. Something came up quite often in the other lists I found that has been bugging me ever since:

The authors of some lists group books about friendship with books about sisterhood.

This suggests a couple of untrue things. One is that men don’t have friendships. None of the lists included books about brotherhood grouped in with friendship, only female friendships. And, while, yes: The literary world is a bit bereft of fiction about male friendships (tell me one if you can! I thought of a couple but really not many), men still have friendships. Are they less influential or impactful than women’s friendships? I’m not sure I’m qualified to say. Maybe the dearth is because of men’s homophobia; writing about male friendship might teeter into “are these dudes gay?” territory, whereas women don’t have as many of those fears. (In general.) We do form intense friendships that are intimate (without being sexual) and we rely on our friends in emotional ways.

The second is that all female relationships are the same. By suggesting that friendships are the domain of women (because sisterhood is also about women), the creators of those lists group make women’s relationships with other women into an amalgamous mass. Like, you know, forming strong relationships with other women is just, waves fingers, one of those things women do, like baking bread and having babies.

But they are not the same.

If you had asked me two years ago how I thought friendship and sisterhood were different from each other, I would have said that friendships are more precarious. They are more easily lost or damaged and can sometimes just fade away. Some friendships exist in your life for a season, some last for decades, but the potential for them ending is always there. But sisterhood, I thought, was different. You might argue or disagree with your sister, but there is something in the relationship that requires you to always be emotionally invested and involved with each other. Genetics? Shared history? The fact that, in fiction about sisters, the relationship is always stronger than the trauma and, in the end, never goes away?

I thought sisterhood was a flower that blossomed your entire life. Even if it was sometimes complicated or painful, it would always exist with its fragrance a steady thread of beauty running through all of your days.

I believed that despite the fact that I don’t have a close relationship with my oldest sister. Her struggles with addiction and alcoholism have been too much for me to incorporate into my life, so I have distanced myself from her. I forgave myself for this by acknowledging that, in truth, my own life is complicated, messy, and sometimes overwhelming. But I always felt like a bad person for this, deep down. That my handling of that relationship was one of the things that would make my heart heavier than a feather at its weighing. (Even though I still, even with that feeling, even with the persistent what would Jesus do refrain in my head, don’t know how I could change how I handled it.)

But in the past 18 months I have learned in deeply painful ways that the enduring nature of sisterhood I assumed was an absolutely certainty is not, in fact, a feature. If sisterhood is a flower, it can be uprooted and tossed into the compost bin. There is so much deep shame in knowing that what I thought was a flower was, to the other person, a noxious weed.

This loss of sisterhood has impacted every other relationship I have now. I have pulled away from many people I love because I do not trust them to not pull away first. When there is any hint of conflict I get deep-down terrified, certain that this person, too, is about to discover why they don’t want me in their life. Coworkers, neighbors, friends, family members, husband, even my own children: I don’t really know how to trust any relationship now.

Because if your sister can reject you, who can’t?

So those lists mingling sisterhood with friendship—not the lists themselves but the concept that they are similar enough to be interchangeable—were an unexpected detour in my healing process. (If one can “heal” from this, which I don’t believe; it might hurt less but I don’t think it will ever stop.) It has led me to a bit of understanding of why this has been so painful.

A friend is different than a sister.

A sister might remember changing your diaper. She knows the conflicts you were raised with and the memories of joyfulness that inform your present. She knows some of your secrets that even your best friend might not. If she loves you it might grow out of true affection or it might grow out of family obligation and shared history, nothing more. You grew up in the same soil (or, at least, the same field) but you are not the same flower and maybe that’s where the tension is. Or at least some of it, because no family is perfect. I can’t really explain or understand why my sister uprooted our relationship but it has to do somewhat with that same soil, with the fact that I was mean to her when we were little, or that she competed with me for our mom’s attention and love, or that she saw our adult reliance on each other as an unhealthy, codependent malignant outgrowth of her painful childhood. You can share experiences and hobbies and running socks in a pinch; your relationship can have some of the markers of friendship but at its core it is based on that shared soil. And I guess in our case the soil was too contaminated to grow anything healthy. (Even if I loved the illusion of the thing I thought we had cultivated together, it wasn’t beautiful or valuable for her but just a constant reminder of the traumas of our childhood.)

A friend is different. She has seen you at your worst in different ways, she’s probably listened as you dissected your childhood traumas (as you have for her) but she doesn’t share them. (She has her own.) The intertwining of lives comes, in a friendship, because of experiences you choose to have, not ones you were forced into because of the accident of birth. You aren’t forced by circumstance to share intimate things but choose to. Your shared interests form the core of the relationship even as the traumatic experiences strengthen it. This isn’t to say that friends don’t go through trauma together. We absolutely do, but because we were together in the difficult experience because we decided to be friends in the first place—rather than just being together because you are in a family—the outcome of the trauma feels, somehow, a bit less painful.

A friend chooses to stay while a sister has to.

Until, I’ve learned, you are old enough to understand you don’t have to. You can be a sister and still choose to leave. Our shared genetics and history don’t preclude my sister’s choice. She can (and did) choose to remove herself from our relationship. Her choice doesn’t take away the shared genetics so in that sense, yes, I am still her sister. It does change my relationship with our shared history, as it meant something entirely different to me than it did to her so I can no longer trust my relationship with my memories, either. She is now not only a person who I shared a childhood with, both the happinesses and the traumas, but a person who has chosen to cause me trauma. (Is that payback or karma for the fact that I was a mean sister when we were kids? I can accept that. Except—we are not children now, and the choices I made when I was six or twelve or even 15 were less cognizant and purposeful than those one makes in middle age adulthood.)

Is the difference, then, choice? Why would anyone choose to cultivate a friendship with a person who was toxic in some way, or stay in a friendship that caused them pain? They wouldn’t. But, generally, people do stick with their sisterhoods, even if a sister is toxic. They find a way to make some sort of connection, even if it’s just liking each other’s social media posts or sending a happy birthday and Merry Christmas text. Not absolute silence.

Unless the sister’s toxicity is just too overwhelming. This would be easier if I had a clear understanding of my toxicity to her, but I can’t explain it even to myself because she didn’t tell me, just said we don’t align anymore. The pain, then, is based partly on the fact that by choosing to reject our sisterhood she negated its specialness. Sisterhood is not enduring, my sister has taught me. It’s just like every other relationship, even if all the books and movies and other actual families say something different.

Would I be any less devastated if my closest and longest friendship suddenly ended? If that friend chose to end our relationship?

No. Not in amount of grief.

But the texture of it would be different. Just as the textures of friendship and sisterhood are different (despite my sister’s insistence). Because there are examples everywhere of friendships ending, but who else has an example of a sister breaking up with her sister? (I ask that with sincerity. I feel like I am the only person in the history of people who has been rejected by her sister.)

None of this changes anything that has happened. The understanding hardly ruffles the texture of this specific grief. But somehow it also helps. Knowing that this hurts this way BECAUSE we were sisters, not because our sisterhood had friendship-like qualities.

And I wrote this so I could acknowledge that losing a sister in this way is uniquely painful. I never wanted to learn that sisterhood can end, but it is what life has taught me.

What my sister has taught me.

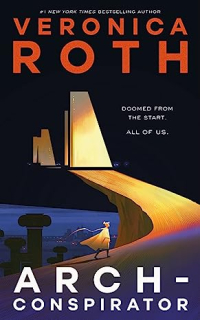

At any rate, I absolutely had to read Veronica Roth’s novella, Arch Conspirator, when I found out it is a futuristic, dystopian retelling of Antigone. I was so excited to read it that I put it off for a few months, because I worried I’d be disappointed.

At any rate, I absolutely had to read Veronica Roth’s novella, Arch Conspirator, when I found out it is a futuristic, dystopian retelling of Antigone. I was so excited to read it that I put it off for a few months, because I worried I’d be disappointed.