The Secret Truths about Being a Librarian

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

My sister Becky and I were talking a few days ago about my job. She wondered if I ever just wander the library stacks, picking out books at random, just because I’m just there, all the time, at the library.

And here is the truth about being a librarian: You lose some of the magic of libraries when you work at one.

Not all of it. I still sometimes have to pinch myself when I realize: I WORK AT A LIBRARY! I get to order books and take care of books and help people find books and talk to people about books.

Being a librarian is, I've decided, a calling more than it is a job. And many librarians are kindred spirits.

But when you love books and then you become a librarian, even though you gain many things, you lose some things, too.

When books are your job, it becomes impossible to separate reading from your work. (Because librarianship is a calling, remember?) Even when you just want to read a book, there is a part of you thinking about that book’s place in the library. Who might you recommend it to? What book list would you put it on? How could you tell more readers about it?

When you work in a library you can't smell the library smell anymore.

And because I have a to-be-read list that is unimaginably long, I never wander the stacks just looking to see what I might find. I no longer read books serendipitously.

Sometimes, if it's slow at a reference desk and I'm at the end of my librarian patience, I might wander over to the stacks, pull out a book I love, and then read a few pages.

But a TBR this long isn't going to make itself. (Nor are any of the one million tasks librarians do going to do themselves.)

Here's another thing, though. When you work at a library, you see so many books. You discover books while you’re working on your collection. You read book reviews and book websites so you can stay on top of what people are reading. You learn as much as you can about as many different kinds of books as possible, because there’s no way to read every book (nor do I want to), but you do want to help every patron find the book they need or the one they will love.

So all that reading about and researching books? Means as a librarian (a person who already loves books and reading) you fall in love with so many books. And I don’t know if this is true of all librarians, but for me, I want to take them all home. (Even though I know I cannot possibly read everything I want to read.)

I got my current library card in July of 1992 and since then I've checked out almost 8500 items.

I REALLY wish I would've noticed how many I'd checked out when I started working here in 2008, but I bet that two-thirds of those check outs have happened in the past twelve years. Maybe even three-fourths.

Of course, not all of those items are books. I check out a lot of movies and CDs, too. But it’s mostly books.

But here’s another truth about being a librarian: sometimes I get tired.

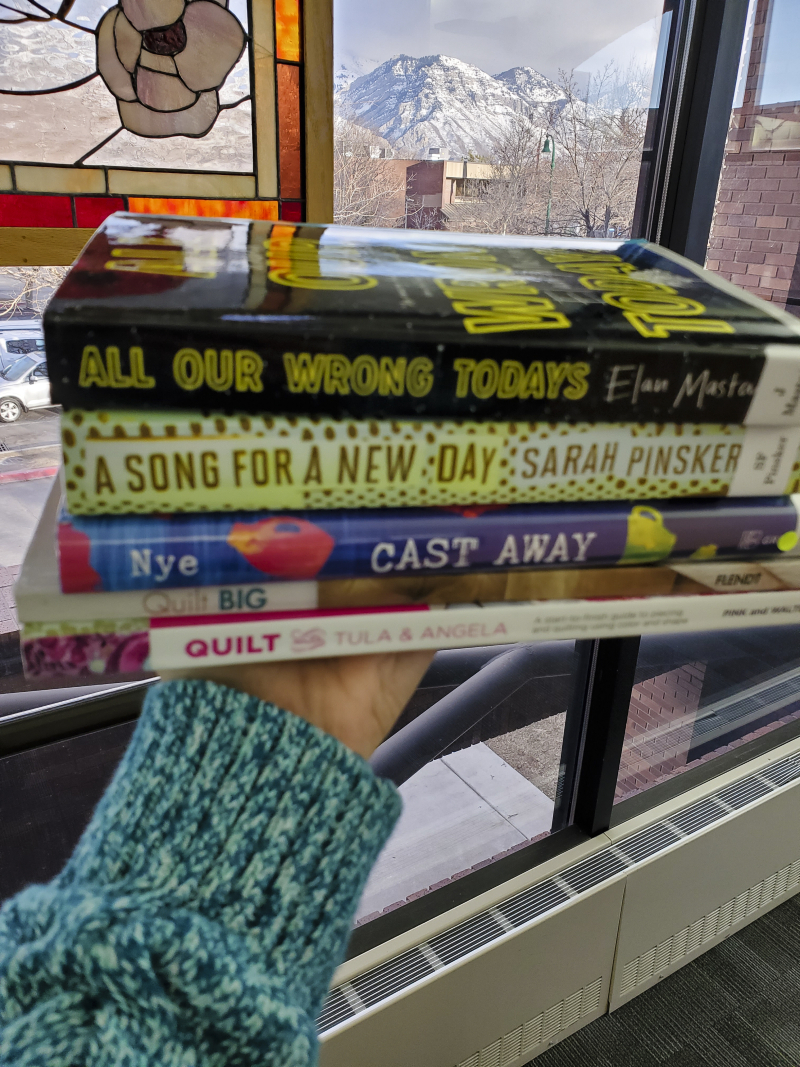

Really, “frustrated” or “annoyed” might be better words. In some ways it is sort of a stressor: knowing what all of the new and hot books are, and the feeling of wanting to read them (again, not all of them, because I still have my own tastes) and join in on the online/social media conversations. So I bring home more and more books, or my hold list grows longer and longer, and I read two or three books a month and then take the rest back.

(And that’s not even considering the books I buy!)

It is illogical, bringing books I never finish back and forth from the library. Just because I love them. Just because I want to read them. Just because everyone else is reading and talking about them and I want to be included in that conversation.

Last week, I was talking to Nathan, who is wanting to read more. I gave him some recommendations and then he asked me about The Dark Tower series by Stephen King.

“I read the first three books in that series and loved them,” I texted him. “But I didn’t finish them.”

My dad and I read the first three books together. I mean…we had our own copies (I think I still have mine), but we read them at the same time and would talk about them. He was delighted by the series and his enthusiasm made reading them even better. He especially liked the lobstrosities and sometimes he’d just say “ded a chek?” to me out of the blue.

After the third book in the series, The Wastelands, King took a break from the series. This break coincided with my wedding, working on my degree, and becoming a mom. My dad picked up the fourth book but I didn’t—I felt like I wanted to read other things then. (OH how I wish I had just read those with him, too.)

I told Nathan that at this point, I haven’t finished the series because it makes me sad to read them without my dad. His response?

“Maybe you can read them with me this go around.”

(He is a good kid.)

The next day, I put all of the books I had checked out, except two, onto my TBR list (I keep mine on an app called Libib) and then returned them. I suspended all of my book holds (I have 43 on my list, shhhh, don’t judge) and gave myself stern instruction to not add any more. (I have since added more…but only three.)

The next day, I put all of the books I had checked out, except two, onto my TBR list (I keep mine on an app called Libib) and then returned them. I suspended all of my book holds (I have 43 on my list, shhhh, don’t judge) and gave myself stern instruction to not add any more. (I have since added more…but only three.)

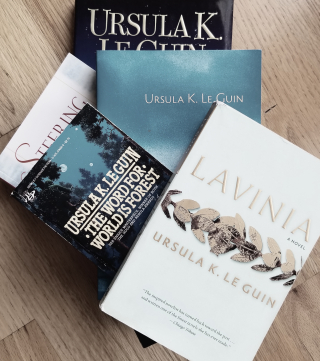

I set myself a goal: when I finish the two books I am reading right now, I’m going to read The Dark Tower series. I’m going to clean out the cupboard where I think my copies of the first three books are, and buy the rest, and then read them. And talk to Nathan about reading them.

I’ll still pay attention to new releases and hot books and what everyone else on bookstagram is reading.

But I really want to take control back in some way. To not have my reading controlled by what comes on hold for me, or what everyone else is talking about.

Books are about story, of course. About going somewhere in your imagination, about becoming friends with created beings. But they are also about relationships. With the story and the characters, yes, but also with the other people who read them. And they are about making connections with yourself, too—understanding something, or sometimes just something as pleasant as a sentence that makes you feel less invisible in this world.

I want to reconnect, somehow, to that primal love of reading I had when I was reading The Dark Tower series with my dad. Before I learned about literary theory and critical thinking and textual evaluation. I want to be able to read outside of being a librarian, but just as myself.

Reading them with Nathan seems like just the thing.