Breaking My Silence About the Library, Or: I Will No Longer Be Shushed

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

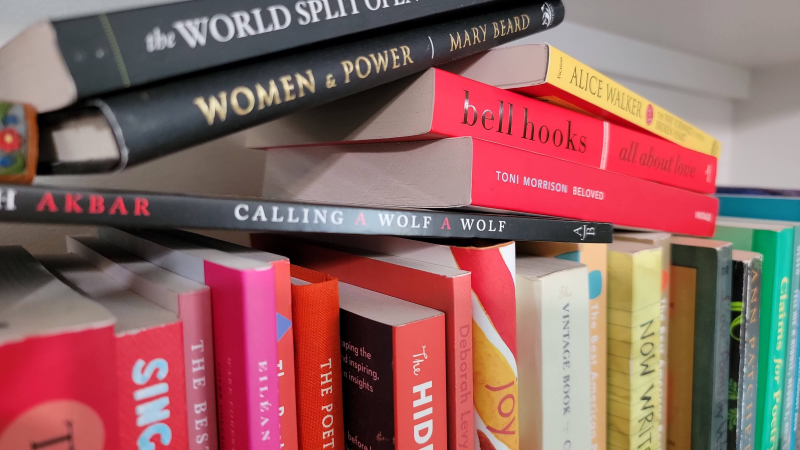

One year ago today I was working on a project at work: pulling books and making a sign for a Black History display.

I wrote an Instagram post about it: why I thought the display was important, how bothered I was that almost every book I wanted to put on the display was checked in, how important I felt it was to have displays like this. How important it is, in a community like the one I live in, where the majority of people are white and the city government is run only by white people. (One of my followers called me racist for calling this out.)

When I wrote that post, and my follow-up blog post, my imaginary audience was any library patron who might have been offended by a tableful of books by and about Black people. I wanted to help that imaginary patron understand that people of all races and identities deserve representation in books in visible ways and that having access to a wide variety of books is important for everyone, even (especially) the majority in power.

“Reading,” I wrote one year ago, “should expose us to the experiences, beliefs, ideas, sufferings, joys, & lifestyles of people who are not like us.”

I believed that then, I believed it ten and fifteen and twenty years ago. I believe it to the very second I am writing this post.

I never imagined that one year after writing that and after making that display, I would be working for a library that isn’t allowed to put up a Black History month display. (Or women’s history, or Pride, or Hispanic heritage or Native American heritage) but here I am, doing just that.

In November of 2021, the city where I lived elected two new city council members and a new mayor. These three people, combined with a third council member who was elected a few years ago, have formed an alliance. A voting block. They pushed for and managed to achieve getting a ballot initiative to have the schools in our city pull out of the school district, using questionable practices and a feasibility study conducted by a company that was created just weeks before it was chosen (by the same council members) to carry out the study.

Luckily, that initiative was voted down.

But that was not the only issue this city council has undertaken.

Since June, it has carried out a subtle but troubling process of censorship at the library.

This has not been done with transparency, but with behind-the-scenes conversations that I did not witness. I can only write what I have experienced, and that is this:

Despite the fact that every librarian I work with believes in the basic principles of librarianship, which include the freedom to read, access to books on every topic, and diverse displays, programs, and collections, we are working at a library where we are not allowed to carry out those basic principles.

We did not have a Hispanic-American heritage display in September. We did not have a Native American heritage display in November. On February 1, the library will open and there will not be a Black History month display.

I also can write that my experience has been that we have been encouraged to remain silent about these issues. The suggestion was that if we did discuss on our social media platforms the things that are happening at the library, we could be fired.

So why am I writing now?

One of my braver colleagues has inspired me. After she left the position she was excellent at, she spoke. The result has been a series of newspaper articles.

Newspaper articles that have infuriated me. They are not cutting-edge reporting. They barely expose any of the manipulative tactics that this city council has used to limit access to library materials.

If you’d like to read them, here is the first one and here is the second.

In the second article, the interim city manager states that my colleague’s statements are “contrary” to the truth. To which I say: Why, then, have we not had any heritage month displays? He also states that “the complaints from a former library employee have identified a lack of clarity in our library policies.”

The problem is not a lack of clarity in library policies.

The librarians are perfectly clear on the policy the city council is pushing: books about people of color and LGBTQIA+ people are not to be put on display.

That is the policy. We are clear on it.

The problem is not clarity. The problem is the policy itself.

It goes against every component of ethical librarianship ideals I know.

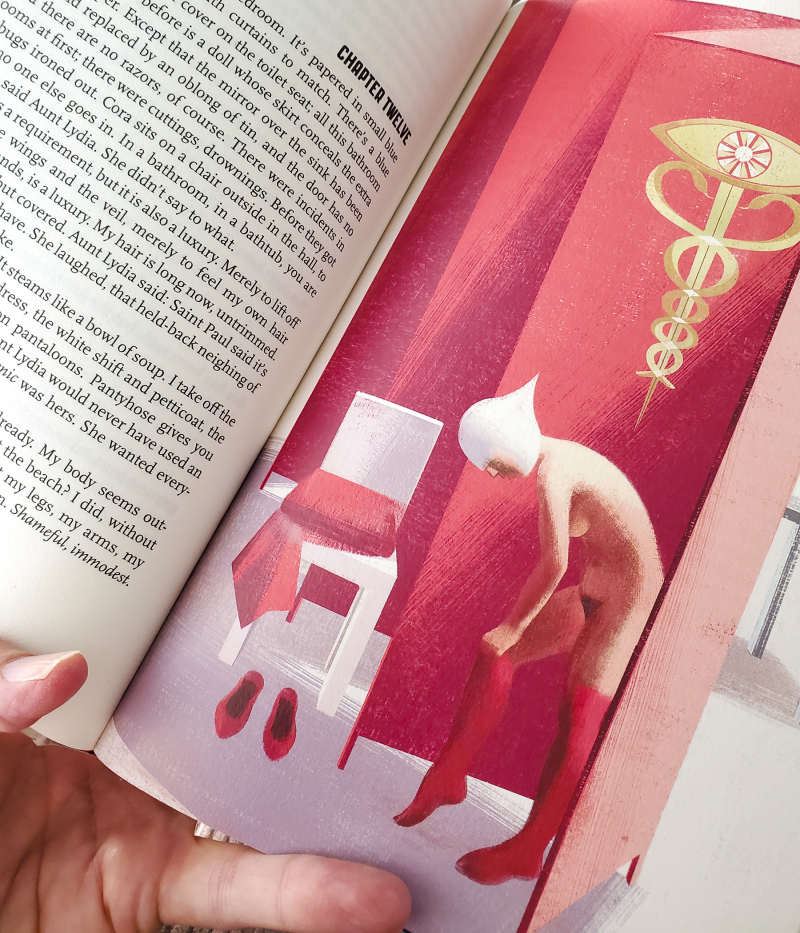

It is censorship.

It is a form of book banning.

This policy has had a damaging impact upon me and upon all of my coworkers.

Likely librarians exist for whom this doesn’t apply, but the vast majority of us are people who are passionate about our work. Librarianship is often wrapped up in “vocational awe”; we see libraries and our work there as a type of sacredness that is inherently valuable to society (which actually leads to a myriad of problems, including accepting pay that is not commensurate to our levels of education and knowledge). We love our work. We love our library patrons. We want to provide them with programs and books that improve their lives.

So to go to work every day with that dedication and knowledge and then to not be allowed to do the work?

It is painful.

And the policy also impacts us in personal ways. Not all of us are cis white males. Not all of us have traditional families. Not all of us are members of the majority religion. We all know someone who is now no longer represented in our library’s displays; some of us are ourselves no longer represented. This policy causes fear, resentment, anxiety, and anger. It does not create a functional working environment where we all feel safe to do our jobs, let alone feel valued by our community or its elected officials.

This morning, when I read the second article, I grew so angry. They had the potential to educate the public as to what is actually happening in the library without fear of career reprisals. They took a soft, unresisting approach. For example, today’s article discusses the fact that Junie B. Jones is the 71st most-banned book series in the United States.

What about the fact that the most-banned book, Gender Queer, is not available on any Utah public library’s shelves?

As I thought about this issue today, as I saw the mayor’s self-congratulatory recorded message being played over and over on the city building’s TV displays, as I did my work under these new restrictions, I came to a conclusion:

I can’t stay silent anymore.

During my almost-15 years of working at the library, I have shared many library stories. I have shared how patrons have made me laugh, frustrated me, insulted me, delighted me. The stories of sharing commonalities despite our differences; the sweet things kids say (“the liberry is my favorite berry”) and the crazy things adults assume (no, it’s no OK to tell me about your husband’s fantasy involving me and my Dr. Martens). Sharing my library experiences has been a fundamental part of my job satisfaction, because I want everyone to know: libraries are necessary places. Libraries are good places. They are full of books but they are really about stories, human stories, living stories. They are—they should be—places where everyone can find knowledge, and it has been a privilege to work here.

I hope I don’t lose my job.

But in a sense, this city council has already taken my job away from me.

Their actions, supported by their voters, have told me that transparency, representation, access, education, literacy, understanding, and empathy are not qualities my community values, and that has broken part of me.

And none of that, none of that matters. My small story is just one part of the library, and the library is the community that uses it.

But by staying silent, I am being complicit.

And as I listen to the news, I cannot do that any longer. It isn’t just about my smalltown library’s problems. It’s a bigger, national issue. It’s the fact that in two counties in Florida, teachers can no longer have books in their classrooms and the governor is proud of this. It’s libraries losing their funding because a few community members don’t think they should have books about queer people on their shelves. It’s about making our society less literate and thus less compassionate.

Censorship is happening right now because the communities using libraries stay silent and thus allow it.

And I cannot abide being silenced any longer.