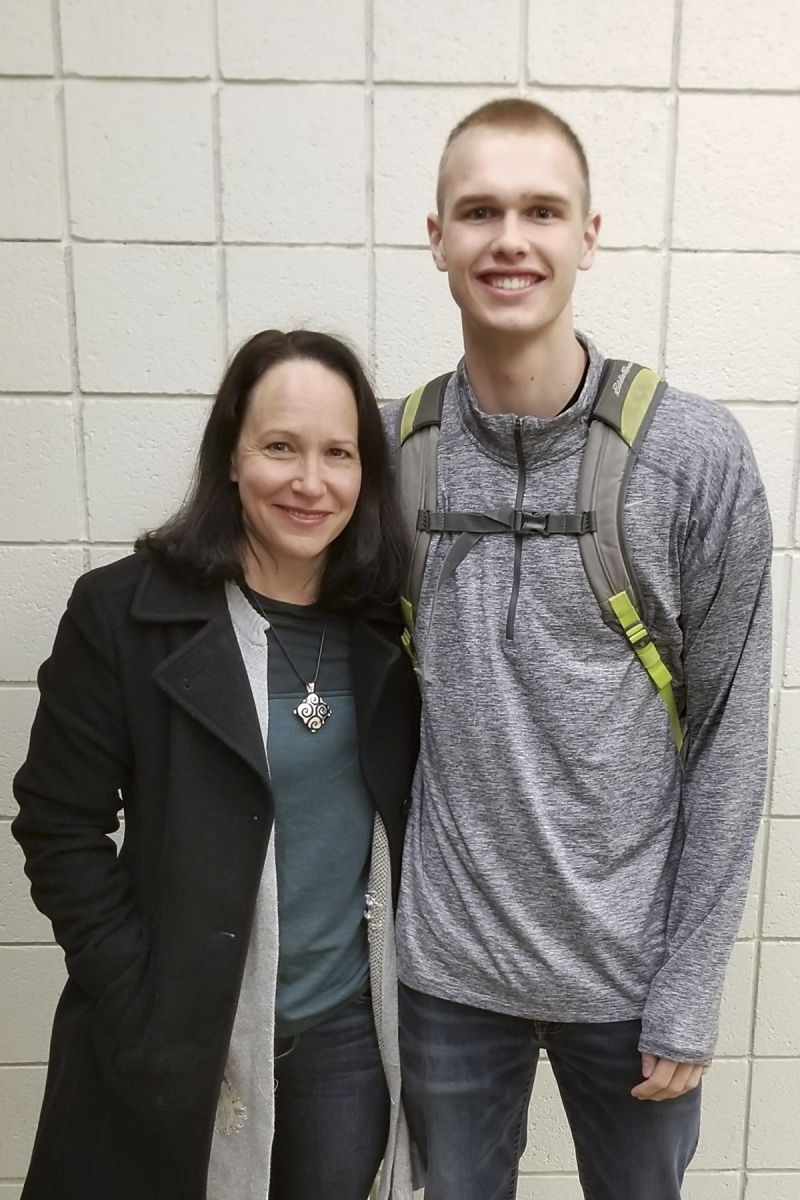

Last week when I dropped Kaleb off at his first day of high school, I had an unexpected reaction. Kaleb and I had a good conversation while we drove to school, mostly joking, and then he told me goodbye and got out of the car. I watched him walk in for just a few seconds—the walkway was lined with cheerleaders shaking pompoms to welcome the students—and then someone honked so I pulled around the driveway and parked for a few minutes. Ostensibly, this waiting was just to make sure Kaleb didn’t need anything, but it was something else, too.

Becky asked me later if I had Feels about taking my youngest child to high school. Shockingly, I kind of didn’t, because it feels so unsure…will he get to stay the whole year? Will it all fall apart? I feel so unsure about how things will go this year with the virus that I don’t think my psyche knew what to do, and so decided on a kind of morose but gentle sadness.

Underneath that, though, was something darker. Something darker and harder and twisted. Something I couldn’t quite label, and it took me a few days, two very strange dreams, and a spark from another conversation for me to start exploring it.

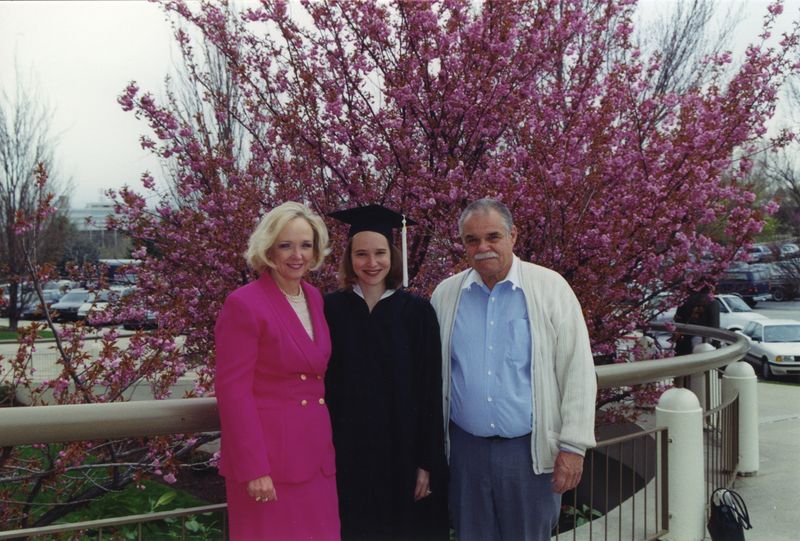

I don’t remember my own very first day of high school. The year I was a sophomore, I was still a gymnast. I went to three classes and then, for the fourth class period, drove twenty minutes to the gym with an older teammate and worked out until six. Then I’d come home, eat, do homework, and start it all over again. That was as normal as my high school experience got, because eleventh grade was a disaster and for my senior year I went to the local community college. English, math, history, biology, art, and Spanish. If you put me back in that high school building, I could walk right to where my locker was. Even though I don’t remember the first day. There are no first-day photos (did people take those in the 80s?) so I don’t know what I wore. I don’t remember which class was first or even how I got there. Did my dad still drive me to school? He must’ve, I guess.

What I do remember clearly was the day of high school registration, which was early in August. I only had one new outfit, because back then my mom would put our school clothes on lay-away until right before classes started. But I loved that outfit, a yellow-and-grey floral print mini skirt and an off-the-shoulder shirt, also yellow. And the white ankle boots I’d gotten when I started ninth grade. My mom dropped me off in front of the school and I walked to where I’d arranged to meet my friends, most of whom lived on the east side and so had come together, given rides by the boys in their neighborhood. My heart sank as I got closer and closer to them, because I realized I was dressed entirely wrong. They all had black on, and they all looked so grown-up and elegant and knowing, while there I was in yellow. My hair felt wrong and my body felt wrong and I didn’t know what to do with my face or my hands.

It’s not that that day was my first time feeling like I didn’t fit in. That feeling had been with me for as long as I could remember. But that day, somehow it felt different. Somehow it felt like an indictment against my…well, I didn’t have the words for it, then, but against my sense of being a woman in the world. It felt like they already knew all the rules, how to dress and how to do their hair the right way, how to talk to boys, how to talk to each other, how to be friends but how to also never trust each other, either.

It was like they had received a letter over the summer that I didn’t get.

When I was in tenth grade, my first year of high school, my parents were fighting all the time. My dad was unemployed and didn’t have a direction to his life anymore. My mom was angry and frustrated at suddenly having to carry the load of being financially responsible for us. They fought all the time and I was alternately terrified that they would get divorced and that they never would. My two older sisters were in different stressful situations which affected the stress levels in our family. (They are not my stories to tell.) My grandpa had died and my grandma, who suffered from dementia, was living in a care home. (My mom was also mostly financially responsible for that bill, too.) We worked hard to make it look, from the outside, like we were a normal, functioning, happy family, but we were not.

Then there’s this: I didn’t really fit in anywhere. My best friend and teammate had quit gymnastics about a year earlier, and I had teammates but no one I thoroughly trusted. Besides, once you’re the girl who has cleaned the gym to pay for her gymnastics lessons, you will never really fit in. I didn’t fit the mold my old friends, from middle and junior high, seemed to fit, the good Mormon girl. My new friends were edgy and rebellious but it was still the same, I still had to watch and pay attention to figure out how I was supposed to act, who I was supposed to be.

So on that auspicious note, my dawning realization that everything about me was wrong, many of it in ways I didn’t even see yet, I started high school. With my mom-dyed hair and the clothes she went in debt for, and before the first term was over I was going to parties on Friday night after gymnastics, and sometimes I drank, and I kissed boys, and I hung out with the kids who did drugs. I kept this secret from my mom and my little sister and my gymnastics teammates, and I was invisible to my old friends, and my new ones taught me so many new things.

By Christmas I had managed to acquire a whole new, almost-all-black wardrobe. I never wore the white boots again.

I went from being a smart, if shy, “normal” girl with a great future in front of her to an angry girl who swore and hung out with the “bad” kids. I did keep my grades up—4.0 my whole sophomore year, even though I had to bluff my way through geometry—and I kept training, until my last meet on the weekend of my 16th birthday.

I didn’t know it, really. My parents didn’t either. But that afternoon at high school registration: that was the spark that started my long, dramatic explosion. Those years weren’t pretty for anyone to watch, and they were brutal for me.

But that is an old story, and not really the point of this writing.

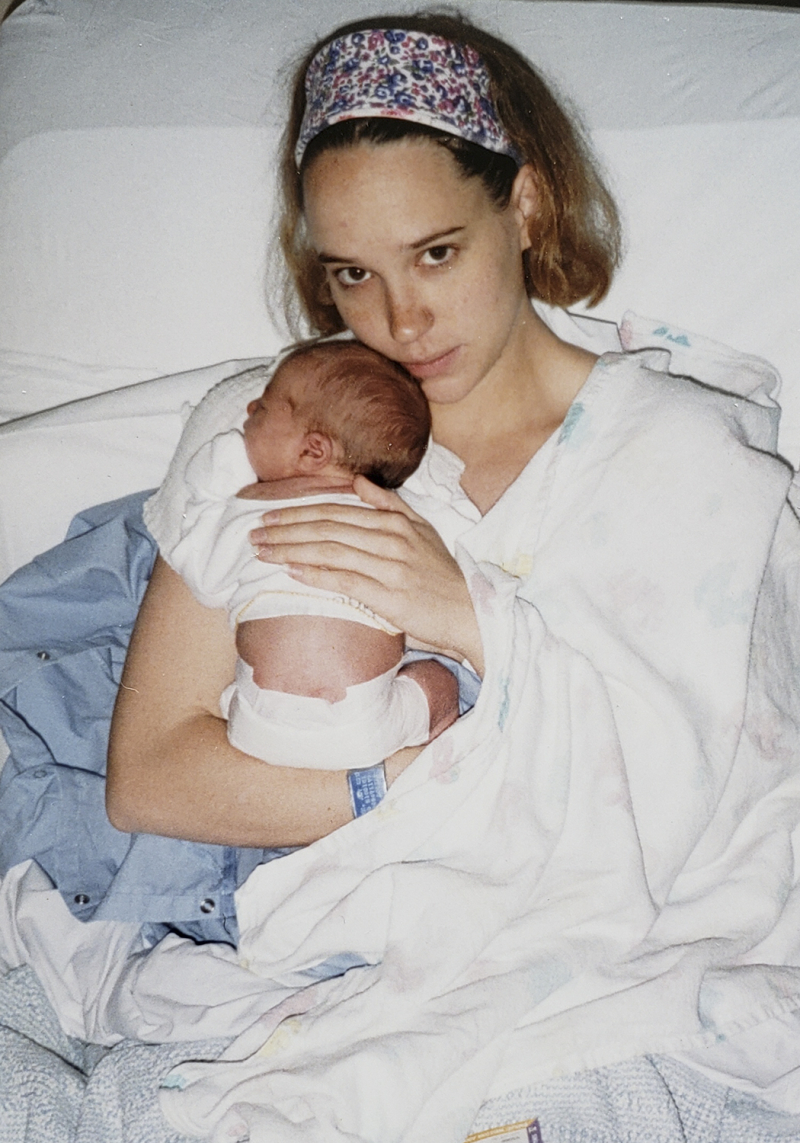

After I dropped Kaleb off, I came home and looked through all of my old photos, hoping I could find my sophomore class picture. I did, and I sat on the floor in my scrappy space and I looked at that girl I used to be. I looked at the picture I had taken of Kaleb before he left. And then I just tried to figure it out. Tried to name that dark, hard feeling.

And I realized: it was anger.

Because no one took care of that girl. When I started to spiral, no one—not teachers or church leaders or coaches or my parents or old friends or anyone—saw anything except I was now “bad.” No one thought…maybe she’s not immoral and awful, maybe she hasn’t suddenly become an idiot. No one thought maybe she is struggling.

They just saw the outside, the black clothes and the cussing tongue, the silver-toed boots and the mood, and they all thought “well, what happened to her?”

Like a piece of beef someone forgot to put in the fridge, I had spoiled. I had gone bad.

“Why don’t you just join the cheerleading squad?” my high school principal advised me (who also happened to be, in the incestuous nature of small Utah communities, my spiritual leader).

“If your problems were as bad as Chris’s, I could understand your behavior, but you have a great life,” my mom told me.

“I wish I could’ve had you when you were ten, but now you’re too old and slow to really improve much more,” my favorite coach told me.

I took their judgement and fired it into shame, and I let the shame fuel my decisions. If I already had that “bad” label, then why do anything else but work to deserve it? If I needed to feel shame for not being from a wealthy family, for having small boobs and muscular thighs, for my high forehead and the fact I preferred books to people—then I took that shame and turned it against myself before anyone else could do it for me.

The tools I had for coping were music, writing, and my messed-up friends. My friends who my mom mostly didn’t like, because obviously it was their fault I had turned bad. In a small way, she was right: they did teach me quite a bit. But I always chose. My choices were based out of fear, anger, shame, guilt, and a bunch of stuff I couldn’t understand yet, but still: I chose.

I worked hard to deserve my “bad” label.

So very, very hard.

I looked at that picture of 15-year-old Amy again this morning. I thought…if I could talk to her, would I tell her to choose differently? To find new friends, to stay in gymnastics, to go to school, to not drink, to never, ever even meet that one boy, and then especially not the other one either.

I’m not sure I would.

Instead, I would tell her that goodness isn’t a black-and-white thing. It isn’t a quality narrowly defined by the tenants of one religion. I would tell her to make her bad-ass choices but to remember: she isn’t bad. She is hurting and she needs kindness, understanding, and judgement, and she will find a few people who will give that to her. I would tell her that she gets to define her goodness, and that she will never fit in but that will be OK, because she also gets to define her sense of self. That it is a life-long process, figuring out who she is, where she belongs, how to love herself.

What choices would I have made if I hadn’t made my choices from a place of shame?

I find myself wanting to tell her many things, but more than that, I want to tell some adult: LOOK. Pay attention. Don’t let her slip through this crevasse she’s sliding down.

I’m an adult now, so I understand how hard that is. It is hard to manage your own adult crap and watch out for your teenagers. I’m not really speaking out of judgement to the adults in my past who failed me.

But that dark, hard, bitter feeling? It is anger. Anger that no one was able to see me behind my actions. That no one extended me grace, so I had to do the best I could with what I had, but I never learned to extend myself grace either. Anger that even twenty-five years later, my mom would still talk about my “dark Amy” years with that tone that brought up all the old shame again. That for her, it was always, until she died, about how hard that time was for her.

Also anger at myself that after 30 years, I’m still carrying around this same old darkness, that I don’t know how to bring real light into my corners, that the weight still turns my back into a crook. Anger that all of my unresolved adolescent feelings were too thick to allow me to feel what I should feel about my youngest child starting high school.

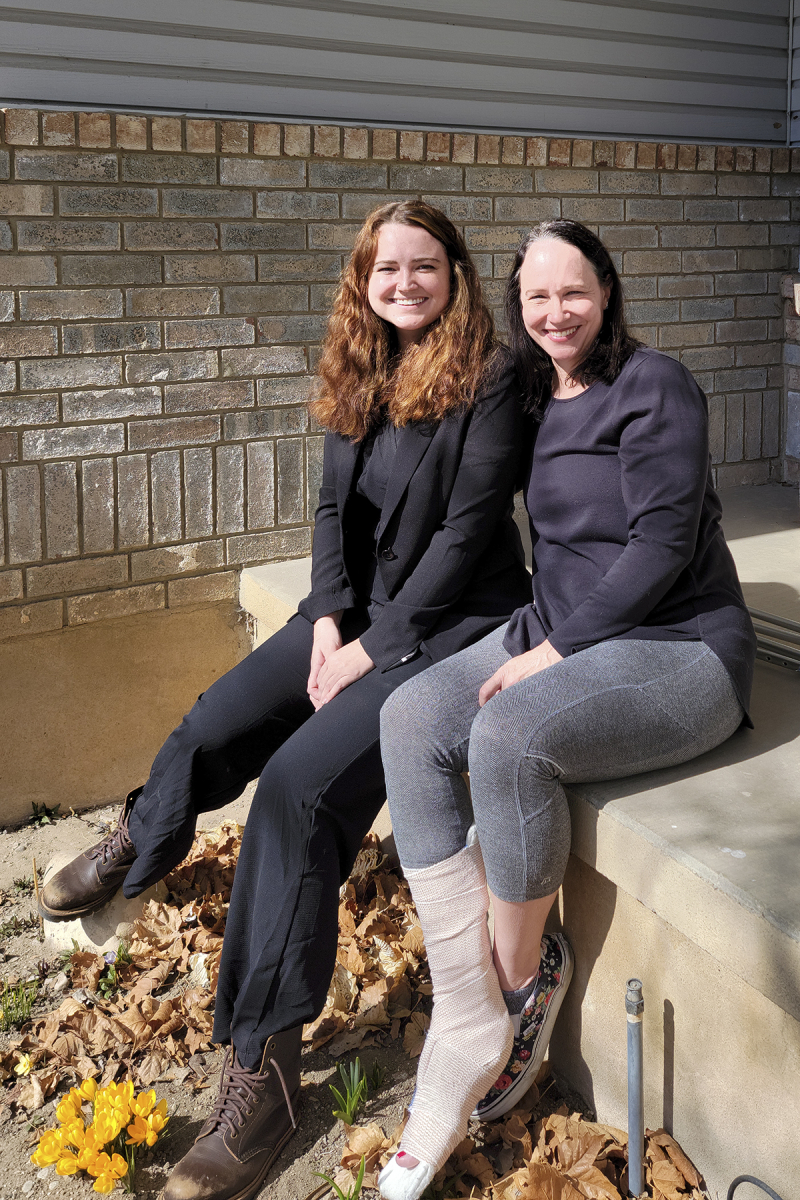

But also a sense of resolve. I will never claim to have been a perfect parent. Maybe, as my mom couldn’t give me what I needed, no one can give their child what they need. Maybe that is inherent to the mother/child relationship. I only know my relationship with my mother and my relationship as a mother. I know I made many mistakes and will continue to do so. But the thing is: I always wanted to help them, each one of them, avoid that feeling. That feeling of wrongness, of not fitting in, of not being enough. I tried to love them through their mistakes, instead of judging them. (I wasn’t perfect at that either, but that was my intention.) I will try to never use their pasts as cudgels in the present.

I only have one teenager left. Even though I’ve already raised three of them, I still don’t know what I’m doing. I still don’t know what the right choices are, because they each need something different. But I want to do better with Kaleb. I want my presence in his teenage years to be one of someone who encourages him to find who he is, not who the world thinks he should be. Someone who will recognize that behaviors aren’t always indicative of the type of person someone is, but a reaction to the types of experiences that person is having.

If there is any saving grace to what I went through in high school, let it be that: let it be a way that teaches me what Kaleb will need as he navigates high school, so that when the three years are over, he arrives at graduation with an intact sense of self-grace instead of this half-buried anger I don’t know how to get rid of.