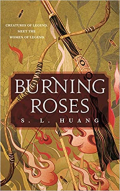

Book Review: Burning Roses by S. L. Huang

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

Some sort of emotion welled within Rosa, flowing out with her tears like an unchecked mountain spring—not gladness, exactly, and not unlike a heart-stopping fear, but also something very much like hope.

I have been thinking about my mom a lot over the past week, likely because it was recently her birthday. Trying to make sense of things, of how our relationship changed over time, of what I could have done differently, of what I wish she would’ve been able to do differently. And also just snippets of good memories. I saw one of her closest friends at Costco and I learned a truth about my family that continues to gnaw at me (in a sardonic sort of way…I could only respond to this by thinking of course. Of course.) I dreamed about her once (but since her death my dreams of her have never been peaceful or good; instead, she is somehow alive and furious at me for thinking she could ever die, let alone sending her body to the morgue, and for getting rid of all of her stuff and selling her house) and I made one of the cakes she made a lot during the summers when I was a kid. My heart felt both heavy and buoyed: conflict mixed with the good memories.

(I feel guilty that even though she is gone I am still hampered by the negative thoughts. Shouldn’t I be able to just let it all go and only remember the good things, now that she isn’t here to defend herself or to explain?)

So perhaps the timing of the novelette Burning Roses by S. L. Huang arriving on my hold shelf was not coincidental.

So perhaps the timing of the novelette Burning Roses by S. L. Huang arriving on my hold shelf was not coincidental.

It tells the story of two characters out of legend, Little Red Riding Hood and Hou Yi the Archer. Both women have grown larger than they began in their respective fairy tales, their stories more intricate and fully lived, dark, and troubled. Now they are each middle-aged, living together and using their respective strengths (gun, bow and arrow) to protect the villagers from whatever monsters come their way. When fire birds arrive, scorching an entire village, they set off on a quest to find the source of the birds so as to stop more from coming.

But this isn’t a book of fairy tales or of quests, even though it contains those. Instead, it is about each character dealing with the mistakes she’s made in her life and figuring out a way to try to atone for them. It is, in fact, a story about beginning to understand, when you are at the end of your usefulness as a mother, the wrong choices you made when you were actively mothering your kids.

(Which is not what I expected at all.)

This is a novelette, so very short (153 pages), and if I summed it up I might just ruin it. So instead I will say how it made me feel.

It is a book that brought me a sense of relief—peace, nearly—about both my relationship with my mom and my relationship with my own mothering.

Because isn’t it so deeply entwined, the way your mom mothered you, the way you mother your own children. You learn how to be a mom, in part, by the woman who mothered you. And I believe we all have things that we think “I’m going to do this differently than my mom did.” When I first had Haley, I knew I would be a fantastic mom. I would give her exactly what I had needed but not received as a child. And of course, as the years went by and I did my best, I made mistake after mistake anyway. I was an imperfect mother raised by an imperfect mother. “She’d regretted every toxic part of herself and her past with vicious self-loathing,” Rosa realizes, which is a realization I have had about myself as well. I didn’t want to be toxic, to make mistakes, to cause any damage, but I still did.

Maybe my own mom also had that regret.

“Love, even more than hate, could always sharpen anger to the keenest of points.” If I didn’t love my mom, I wouldn’t have this anger still with me. Actual love must be about the whole person, not just the good parts; it has to be about knowing—seeing—the flaws, too, but carrying on anyway, and that is complicated and messy. Anger follows. Even after they are gone, or at least for me.

When I finished the book, as I was closing it, I felt…I felt a lifting. A sense of forgiveness, or maybe just the first step towards it, for my mom. Like Rosa and Hou Yi—like myself—she made mistakes. Considering her biggest mistake, Rosa realizes it was “only a clumsy, flawed decision, like so many others along the twisting path that had brought her here.” Not every choice was wrong, not everything was bad, and nothing was truly horrible. My mom, and Rosa, and Hou Yi, loved her children but also wounded them.

I did, too.

There isn’t ever a moment in the book when this is explicitly spelled out, but what it left me thinking was this: mothers always make mistakes, but trying to hide from them or to keep them hidden is impossible. This is because mothering is difficult, and it is difficult because we love our children. And so while we can’t hide our mistakes—while we have to look at them and process them—we can keep working. We can keep trying. We can never give up on loving.

Near the end of the story, Rosa realizes that she “only had the tail end of a single lifetime, but she thought it might be just enough.” I don’t have that tail end left with my own mom, but I do with my children. I know that despite my good intentions I will continue making mistakes, but I will also keep trying.

So maybe this book also brought me a bit of self-forgiveness as well.