Book Tag: Reading Habits

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

I found this book tag on a blog I also recently discovered, Read by Court and thought it looked like a fun list of questions to answer. If you are new to my blog allow me to warn you: “brevity is the soul of wit” is a bit of wisdom I have a hard time actually using, but I’ll try to keep my answers short!

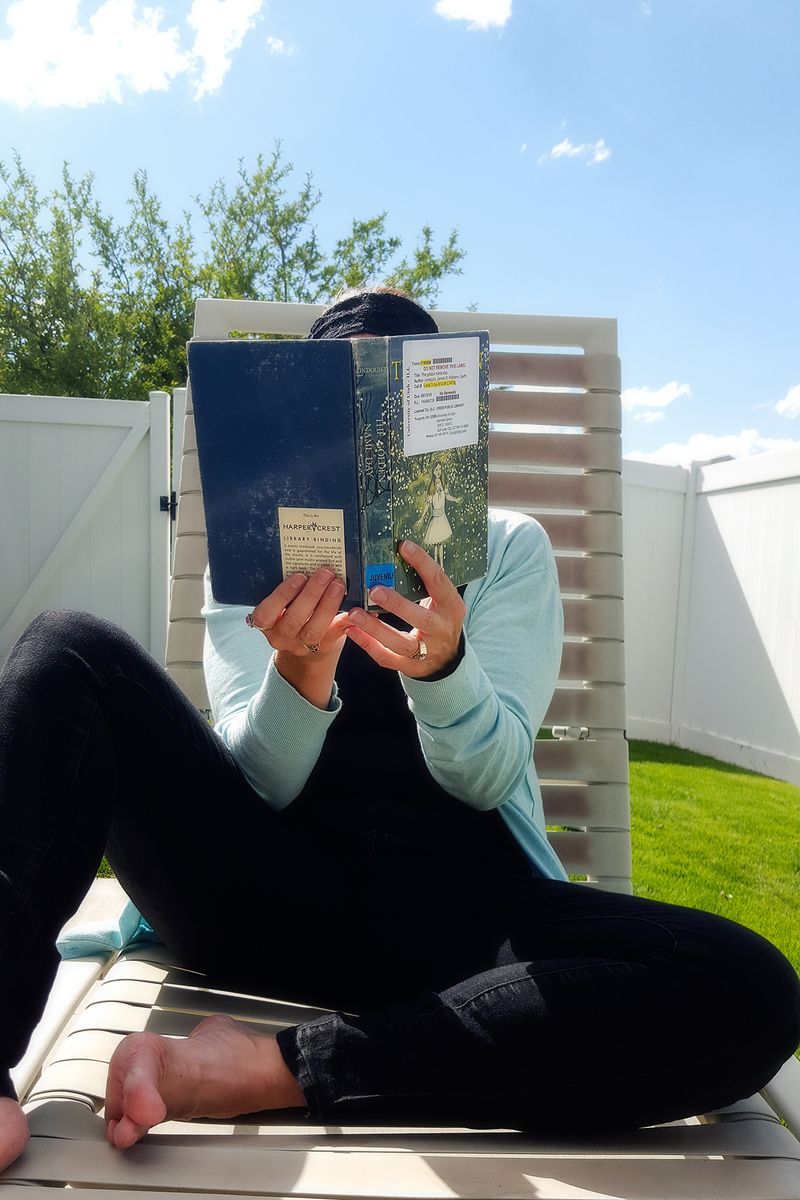

Do you have a special place at home for reading?

Dare I confess: I do a LOT of reading in the bath tub. Not really because it’s my special place to read but because in a house full of boys, I am most likely to be left alone in the bathroom. But tub reading is a life-long habit for me. When we built our house my mom suggested putting a light over the tub because she knew of my proclivity and I’m grateful for that bit of advice all the time! I also read in bed, in the front room, or at the kitchen table. In the summer I like to read outside on the lawn chair.

Bookmark or random piece of paper?

Yes! In theory I love bookmarks and I actually own many, but I will use whatever is near. Often it is little bits of scrapbooking something-or-other acting as a bookmark. I also have piles of images I’ve cut out of Folio book catalogs that I use for bookmarks.

Can you just stop reading or do you have to stop at a chapter/or certain amount of pages?

I can just stop reading. I learned this skill when I became a mom.

Do you eat or drink whilst reading?

Is it even reading if you don’t start with a snack? One of my favorite things when I was pregnant is that my belly allowed me to combine three things I love: I’d get in the tub with a bowl of ice cream and a book. I’d nestle the bowl between breasts & belly, hold my book with one hand and the spoon with the other. Eating, bathing, reading all at once!

Multitasking: music or tv whilst reading?

I don’t require silence when I’m reading, so if someone’s watching TV or listening to music it doesn’t bother me at all. But if I’m alone I would turn it all off.

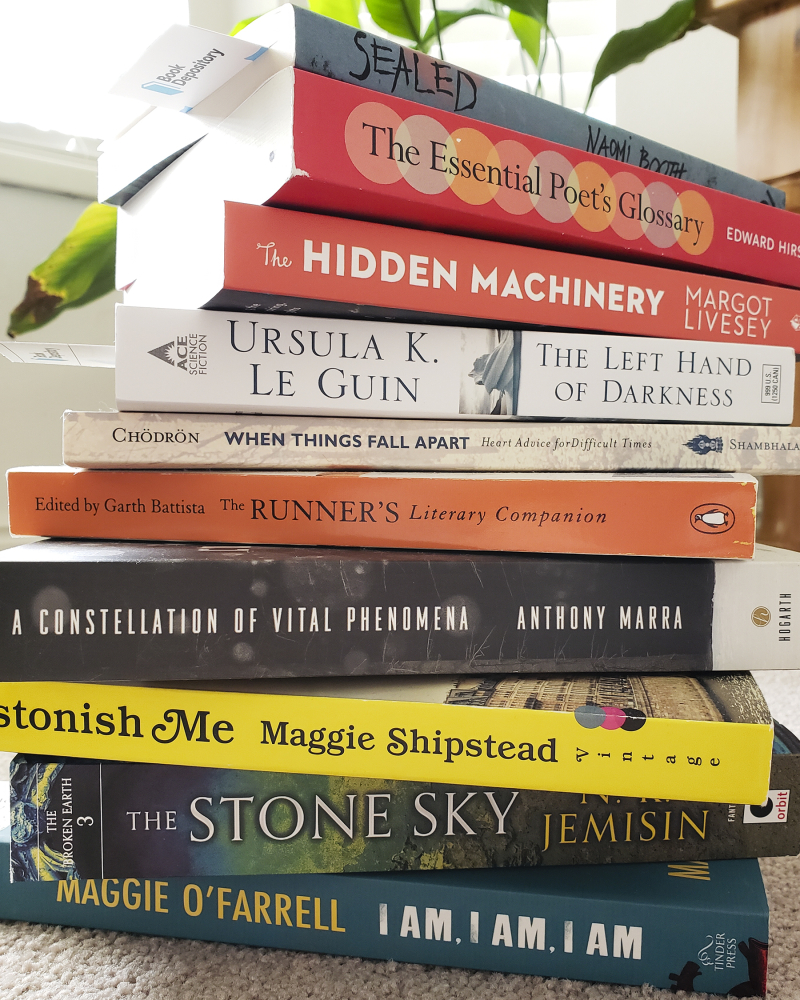

One book at a time or several at once?

I usually have one novel I’m reading in physical form and one I’m listening to on audio. And I am always working on a poetry book or essay collection.

Reading at home or everywhere?

I wish I felt comfortable reading anywhere. Like, wouldn’t it be great if I were at a party and feeling my usual awkward-and-unskilled-at-mingling self, and I could just find a corner somewhere and read? But I think that is generally socially unacceptable. I did sometimes bring my book to family parties at my in-laws’ house, and since they were both readers I don’t think it bothered them, but it did bug Kendell. I do always bring a book (or three) with me on trips.

Reading out loud or silently in your head?

One of the things I loved when I was a teacher was reading out loud to my classes. And I loved reading to my kids. But if I’m reading for myself, I read silently.

Do you read ahead or skip pages?

If I start to read ahead it’s usually a sign that I’m not enjoying the book. The only book I’ve actively skipped pages in was The Martian, where I mostly skimmed the science-y stuff. Also I have been known to read the last pages of books.

Breaking the spine or keeping it like new?

I’m not really OBSESSIVE about keeping the books I own in perfect condition, but I also try to not purposefully damage them either. Is a book simply a story-delivery mechanism, or does it hold value as an object? It depends, for me, on many things. Like, if I’m reading a hardback book I’ll generally take off the slipcover. But I also feel like the books I own are records unto themselves, meaning the process of reading it is part of the book itself, and incidental “damage” is proof of that book’s existence inside of my life, so I actually LIKE if it looks like a book’s been read.

Do you write in your books?

Yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes. I annotate and underline. When I finish a book I often write the date on the back flyleaf and my thoughts. Or if it’s a book in a series I make a list of what I think is important to remember for the next one. If there’s a story about where I got the book I’ll write that somewhere (“I bought this at a used bookshop on Charing Cross Road” for example). Many of my books also have random notes in them, like “eye doctor, 9:30a.m.” and if the book in question went on a trip with me, I write that too and also try to leave some trip-related memento in its pages. And, yes, to answer the unspoken question: I do dog ear my books. (But not the library’s!) Not to mark my page, but to identify pages I want to return to.

When do you find yourself reading?

I don’t have a set reading time, so just whenever I have some free moments. If I’m eating alone for whatever reason I will usually read then.

What is your best setting to read in?

Just somewhere comfy. I believe that books and quilts, like books and snacks, go together, so I like a quilt around if it’s possible.

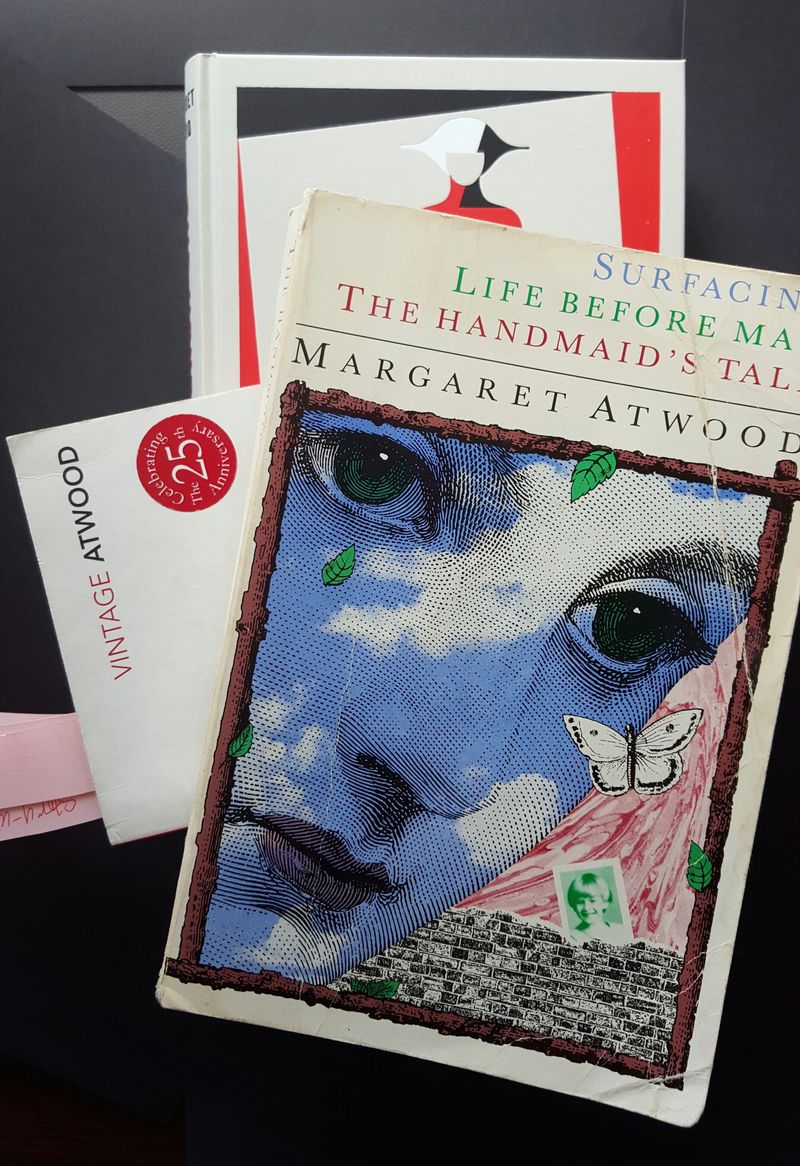

What do you do first, read or watch?

I have actually grown more and more reluctant to watch movie adaptations of books I LOVE. (Like, people who know me assume I must adore the TV adaption of The Handmaid’s Tale, as it is my favorite novel, but, no. I don’t need more story than was included in the book and I’m actually kind of irritated it became a TV show.) It just so rarely happens that the movie version actually jives with the images I have created in my own head that I have started avoiding them. But if it is a book I am only sort-of interested in, I will see that movie only after I read the book.

What format do you prefer: e-book, audiobook, or physical book?

I really don’t like e-books. I like the book in my hand if I’m using my eyes. I have read a few e-books on my phone but I don’t own a Kindle. I do have a growing affection for audio books though. I listen to them while I am quilting, cooking dinner, cleaning around the house, or working in the garden. Also on long runs when I am training for races. I mostly listen to fantasy novels. Also, if I want to read a sequel to a book I don’t remember as well as I would like, I will listen to the audio of the earlier book before starting the new one.

Do you have a unique habit when you read?

I don’t know if it is unique, but I tend to find myself twirling my hair while I’m reading.

Do book series have to match?

If I’m buying the series then yes, I would prefer they match. If I’m reading the library copy I don’t care. Honestly, though, I rarely buy series. I do have my own copies of The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and The Time Quartet, and I bought a lot of YA series when my Bigs were teenagers, but generally I don’t have enough shelf space for all the series.

How do you decide if you’ll read the library copy or buy your own? (I added this question because the previous questions made me think along these lines.)

If I think I’ll read a book more than once, I will buy it. I tend to buy more poetry, essay, and short story collections than fiction. I will always buy Margaret Atwood’s newest books. If I want to have a relationship with the book itself, rather than only reading the story, I buy it. I also really like it when a friend borrows a book I own.

If you read this far, now you know all about my reading habits!