"And Yet You Will Weep and Know Why": Thoughts on My Dad

Tuesday, June 15, 2021

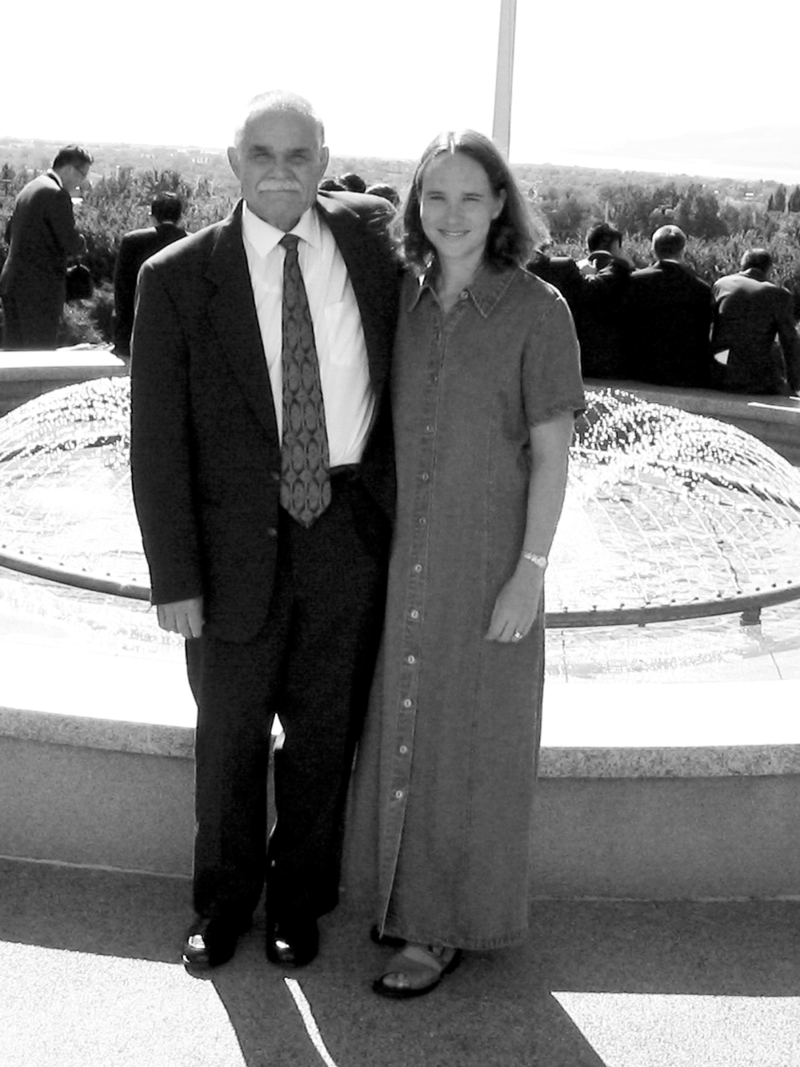

Yesterday I listened to a scrapbooking podcast while I worked in my flowerbeds. The topic was documenting your dad’s stories, and as I listened I had some realizations. The timing was odd for me, as it is June, which holds both his birthday and Father’s day, when I already think about my dad more than usual. This July marks a decade since his death, but since he had an undiagnosed type of dementia, he has been “gone” for much longer…I think we had our last semi-real and meaningful conversation in 2006.

A few days ago, I was at the grocery store, and in the produce section I realized I must’ve come at the grandparent hour, as I was surrounded by old people. Mostly couples, one pushing the cart, the other gathering apples or onions or romaine, but there was one man who was by himself. He looked nothing like my dad but he made me think about my dad. What-ifs starting filling up my mind. What if his marriage had been happier? What if he had found fulfilling work after the steel mill closed? What if he could’ve recognized his inaction not as laziness, as my mom labeled it, but as depression? What if his dad hadn’t died when he was in high school? What if his parents’ marriage had been happier? What if his mom had loved him more? What if he’d skipped football on whatever day his skull was hit too hard, what if he’d skipped football altogether? What if he hadn’t stood in the open refrigerator, depression-eating mayonnaise out of a jar with a soup spoon bent by scooping ice cream from the container?

(I believe all of these things contributed to his early dementia.)

I looked at that old man putting a small bag of red potatoes in his cart and I wondered. What would my dad have been like as a real grandpa? What if he could’ve grown old and achey, his hair entirely white, still talking and telling stories and laughing at off-color jokes? What if he could’ve really interacted and known my children—how would he have loved them, how would their lives be changed? How would I feel, right now, nearing 50 and empty-nesthood and my own aging, if I had a dad I could turn to for help or advice or maybe just a good long phone call about a person he knows from down at the coffee shop?

When I sat down to write this blog post, I thought it would be a list of questions I wish I could ask my dad. Did you ever wish you had a son? How did you really feel about your marriage? Why didn’t you try harder to spend time with my kids when you could? Tell me a good memory about your dad. Tell me a good memory about your mother. Why did we never visit your grandparents’ grave even though we were in the same cemetery every Memorial Day? What did you love about football? What did you love about wandering around in the desert? Were you, like mom, disappointed in how my life turned out?

Or maybe I would write about the realization I had. When I dig into my family history, I am consistently disappointed by the lack of stories about my female ancestors. Even the short life-story someone wrote about the person I was named for—titled “Amy Simmons’ Life Story”—is mostly about her husband and sons. So I have told parts of my story, and of my mom’s and my grandmas’. But I have told very few of my dad’s stories, and all of what I have written down is about me interacting with him, not him as a person independent from being my dad.

What surprised me about writing this—knocked me on my back, so to speak, with an absolute flood of tears—is how raw it all still is. How I have put away unexamined so many ugly and painful truths about our family, simply because he died. I haven’t really processed any of it, my parents’ shaky marriage and how it impacts still, to this very moment, my own. The way I loved my dad and I know he loved me but how I also have a lot of buried anger at him, and how if I could hold it up and look at it, I think it would look a lot like the anger my own children must have for me. How I am just like him in many ways, not all of them positive.

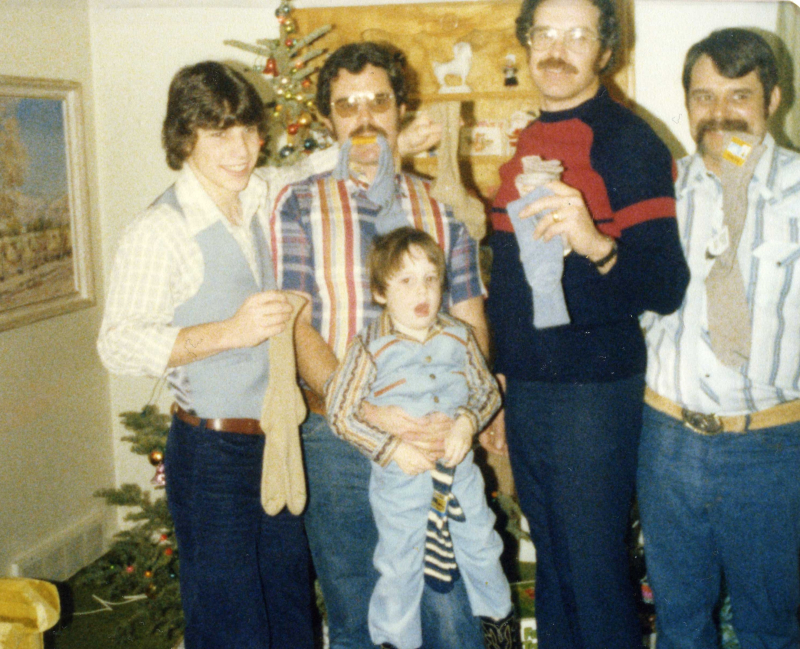

Ten years ago, my dad died. I thought it was a life event, a thing that everyone has to face, and while it was unfair that I had to do it at 39, at least I had good memories to hold on to. Those summer weeks in Lake Powell, the look on his face when I stood on a first-place podium after a gymnastics meet (which was the same look when I stood in 9th place or in no place at all), that one time in the car driving him home from the airport with Haley in her carseat and he sang “you are my sunshine” with her and that’s the only time I ever heard him sing.

I thought: he died and I miss him and so I have to let go of all of the rest of it, the complications and the disappointments and the wounds and the struggles. But ten years later, if I let myself think about it, if I stop to be within it:

I only put the things on a shelf. They are still there, unprocessed, unspoken, still being carried around. His death didn't negate them and it didn't heal them.

I still miss him.

It still doesn’t feel any better since he started leaving by stopping speaking.

None of it is resolved, none of it is repaired, and it can’t ever be. Not really. I can work through my own issues over our history, give voice to my own angers and sorrows, write down what I loved about him and my favorite memories and the fact that I will likely never go back to Lake Powell because Lake Powell is my childhood and so it can’t exist without him.

But me processing it doesn’t help him. It doesn’t fix his wounds and his damage and his anger (which he never, ever voiced).

Me processing it doesn’t give him the chance to go to his brother’s 80th birthday party last month.

It doesn’t let him be at my kids’ graduations.

Or let him have a good, long, loving but hard conversation with my son who is his generational twin.

Or stand in the grocery store as an old man buying potatoes.

You live with it—grief, loss. Sometimes it feels less heavy, but I think that is only because life, the living of your life, lets it weigh less. And then something happens, some small thing, a stranger in a store, and you start to feel the weight of it. I don’t want to not feel it, honestly, because it is the only way I have of interacting with my dad anymore. I miss him and part of me will always be mad at God for not letting him have more joy in his life.

And I guess I just needed to put this out into the world today:

I wish my dad was still here.