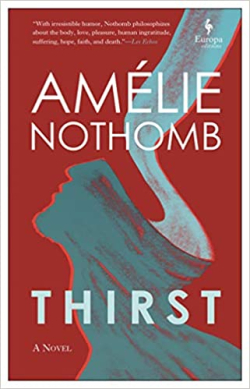

Book Review: Thirst by Amelie Nothomb

Thursday, May 20, 2021

If you reproach your departed loved ones with not appearing before you, do not forget that you are the one who needs them and not the other way around. When we truly love someone, do we require that they sacrifice themselves for us? Isn't allowing those we love a bit of selfish tranquility the finest proof of our devotion? That takes less effort than you might think, merely trust.

In truth, if your departed loved ones remain silent, be glad. It means they have died in the best way. That they are having a good experience of death. Do not infer that they do not love you. They love you in the most wonderful way: by not forcing themselves to go into unpleasant contortions for your sake.

"What is your favorite kind of book to read?" is a question I am asked often, as a librarian and a life-long reader and a person who tends to bring up books a lot in conversation. This is actually a difficult question for me to answer because my real preference— "anything well-written"—sounds snobby and also sort of vague but incredibly precise all at the same time. I can't bring myself to just say something like "fantasy" or "historical fiction" or whatever.

So I try to turn the question around on the questioner. "What do you love to read?" And while it is totally unfair of me, seeing as it is difficult for me to answer that question, I have a very-very-much unfavorite answer:

"The scriptures." (Or, "The Bible." Or, if we're in Utah, "The Book of Mormon.")

Probably this says a lot about me, and perhaps it is horrible of me to even confess, but, I confess: I don't enjoy reading the scriptures. I get caught up in small details that don't make sense to me. (Like, if the sun was created on the fourth day, why are the time periods before that also called "days"?) I get annoyed by the things that happen and the choices people must make, by the violence and, most of all, by the patriarchal view of the world. I cannot relate.

Don't get me wrong. I understand the reason for reading scripture. I even understand figuring out how understanding those ancient stories might make me a better person. There are scripture passages I love and I even have a favorite scripture (Isaiah 12:3). There are many stories in the scriptures that I love as well.

But I don't love reading the scriptures.

What I do love, however, is a good retelling of a scriptural story. (I also love retellings of mythologies and of Homer's and Virgil's epics and of Shakespeare and even of Austen under the right circumstances.) The Red Tent by Anita Diamant is one of my all-time favorite novels; Mark Twain's The Diary of Adam and Eve gave me a profoundly altered understanding of my relationship to God, and I still sometimes wake up from dreams about Noah's wife inspired by Naamah. I have favorite poems about Mary and Eve and Sarah and Bathsheba.

Last week at the library, I was going through a pile of new books, sorting them into groups depending on which display shelf I would put them on, I came across a thin, blood-red book called Thirst, by Amelie Nothomb. I read the inside cover: "In a first-person voice as entertaining and irreverent as it is wise, Northomb narrates Jesus's final days, from his trial to his crucifixion to the resurrection." And I read the first page, which describes the trial of Jesus. The first witness is the couple from the marriage at Cana, who complain that Jesus's miracle humiliated them by its timing, forcing them to serve the better wine after the inferior and making them a laughingstock. Other recipients of his miracles also testify, complaining about how they were unfair or changed something else other than what was intended.

Last week at the library, I was going through a pile of new books, sorting them into groups depending on which display shelf I would put them on, I came across a thin, blood-red book called Thirst, by Amelie Nothomb. I read the inside cover: "In a first-person voice as entertaining and irreverent as it is wise, Northomb narrates Jesus's final days, from his trial to his crucifixion to the resurrection." And I read the first page, which describes the trial of Jesus. The first witness is the couple from the marriage at Cana, who complain that Jesus's miracle humiliated them by its timing, forcing them to serve the better wine after the inferior and making them a laughingstock. Other recipients of his miracles also testify, complaining about how they were unfair or changed something else other than what was intended.

I read the first two pages in one rapid gulp and then I decided the book would not go on a display shelf yet, but come home with me for a few days.

This is a short book, only 92 pages. But it changed me irrevocably.

It fits my requirement—"well written." Christ's voice in this book is unique, both sardonic and sincere. He reminds me a little bit of the Adam in Twain's book, except there is no silliness, just wisdom in his type of innocence.

But it also fulfilled the thing that my absolute favorite books do: they put into words—by way of story, character, plot—ideas I have considered but not been able to put into words of my own. They answer a question I have been struggling to form. They help me see the flaw in my thought, or give a clue to understanding. Truth, I believe, is like the broken mirror in the fairy tale, scattered around the world, sharp and perhaps dangerous but always worth seeking, and sometimes a book is a piece of the truth.

Lately I have been thinking of the scripture Matthew 7:13, considering what "narrow" means. I haven't found the exact way to explain my thoughts yet, and Thirst does not reference that scripture, but it still helped me understand the impulse behind this question, which is really the question that has guided me for the past five or six years: What does it mean to be a good person? What is "good" anyway? The Christ in this novel has ideas on that, and he shares them, and these ideas helped widen my path of thought.

There are many quotes and ideas I could share from this slim novel—Christ's interaction with Simon of Cyrene is such an amazing moment, for example—but the one that first shook me hard was this. Christ is thinking about the couple's testimony, because the miracle at Cana is his favorite, and about the miracles he performed in his life. He tell us: "Later on, I gave it some thought, and I did not approve of my wondrous feats. They gave the wrong impression, this was not what I had come to deliver; love was no longer free, it had to serve a purpose." Christ's love—in the novel but also in the sense that I am just beginning to understand it—doesn't exist for miracles or even for saving us, but just as what it is. Love. Love. That is the reason the way is narrow, because it is simple.

I read the library's copy of this book, but I will be buying my own. I will reread it and underline all of my favorite parts. And then I will get obnoxious with it, I think. I think I will loan it to my friends. I will ask them to read it, too. My copy, I mean. And underline what they love. And tell me how (or even if) it changed them.

Some books come into your life at exactly the right time. For many people, this happens with scriptures. For me, it happens with literature. In this sense, some books are a sort of scripture for me, sacred writings that help me understand how to be in the world. Not all—not even many—books are sacred like this. So I am always grateful when I find one.