Book Note: Under a Painted Sky by Stacey Lee

Sunday, September 13, 2015

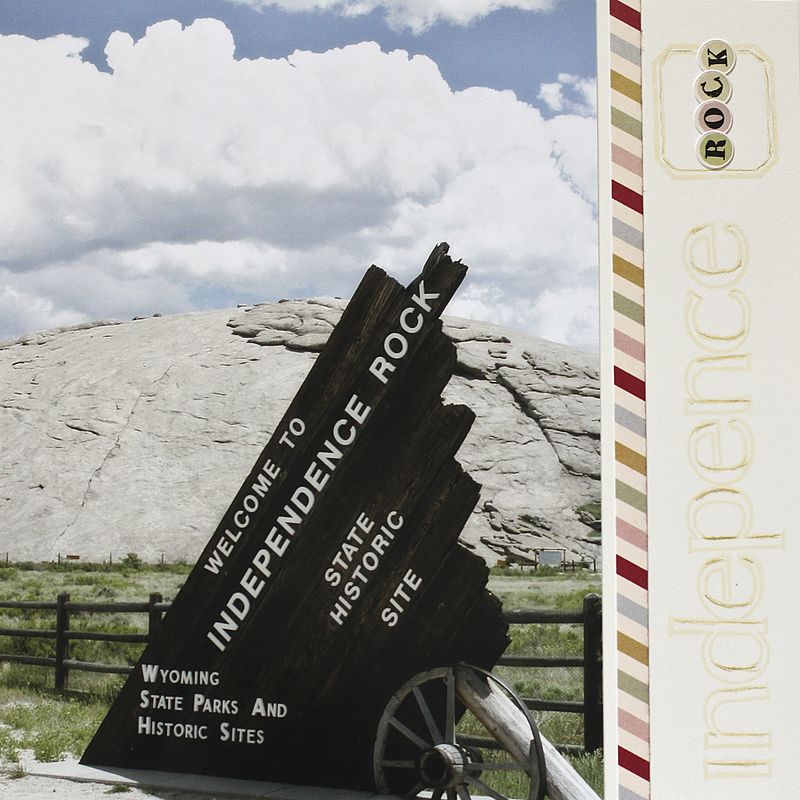

One of the highlights of my life was the day I stood on the Oregon trail.

(I am wearing pioneer clothes because...well, you know. Pioneer trek reenactment. And people say Mormons are weird.)

This was when I went on a pioneer trek with the youth in my church. It was a highlight because I have always loved pioneer stories, but before doing research for the trek, I had no idea of just how many people I am descended from who crossed the country on the Oregon trail. Those rare times when it seems that history and my life right now overlap are moments that are full of meaning to me; they are memorable and change my focus in ways I didn't expect. Walking on the exact same ground that my great, great, great, great grandmother also walked (as well as many other great-something grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles) felt holy to me. They became much more real to me.

But even before I knew so much about my ancestors, I was drawn to trail stories. Not so much Westerns (in the Louis L'Amour tradition) but novels about people traveling across the country in epic journeys. Come to think of it, the only Western I really love, Lonesome Dove, really is more of a epic pioneer story than anything else, even though the "pioneers" aren't a traditional family.

At any rate, when I read about Under a Painted Sky after a patron suggested we get it for the library, I wanted to read it immediately. It is the story of Samantha, who is living in St. Joe, Missouri, with her father. They moved there after her mother died, when they left New York City to start over. Half Asian, half French, Sammie seemed to fit in OK in New York, but in St. Joe she is an anomaly, viewed with suspicion. When her father is killed, she has to flee St. Joe.

At any rate, when I read about Under a Painted Sky after a patron suggested we get it for the library, I wanted to read it immediately. It is the story of Samantha, who is living in St. Joe, Missouri, with her father. They moved there after her mother died, when they left New York City to start over. Half Asian, half French, Sammie seemed to fit in OK in New York, but in St. Joe she is an anomaly, viewed with suspicion. When her father is killed, she has to flee St. Joe.

Luckily, she meets Annamae, a run-away slave also trying to escape from St. Joe. Striking up a fast friendship, the two decide to travel to California together on the Oregon trail, pretending to be boys—named Andy and Sam—in order to escape suspicion. (They are both likely to show up on "wanted" posters.) A couple of days outside of Missouri, they strike up a friendship with a group of three cowboys, Cay, West, and Peety, and conspire to stick with them in order to learn the skills they need to survive on the trail.

I loved this book.

Sure—one might complain that Andy and Sam don't really make convincing boys, and it's a little bit far-fetched that they aren't immediately uncovered. But I just chose to go with the conceit because I enjoyed the story so much. It is a plot made richer by interesting characters and the addition of Andy's straightforward faith and Sam's intricate knowledge of literature, music, and Asian philosophy. (Her father insisted she be educated while they were living in New York.) They characters have all sorts of adventures, from surviving a cattle stampede to crossing rivers to saving their horses from wild mustangs.

But my favorite part of the book was Sam and Andy's friendship. If you are lucky in your life, you come across two or maybe three people with whom you immediately connect, and this is how their friendship is. It starts with a mutual need (escaping St. Joe) but grows into something much deeper and valuable. They have to learn how to trust each other and how to communicate around their cultural differences, but each girl has something the other can lean on. As I think more YA novels need strong girl friendships, I loved this.

It's also a book full of adventure, history, and (yes, or course) romance. I gobbled it down in less than two days and I've found myself falling into good memories of the story as well. It felt like it ended with the possibility of a sequel—it wrapped up well and didn't leave me hanging, but I can see the story continuing on. (In fact, I really hope it does!) It reminded me of that day I walked along the Oregon trail and of the sacrifices and hardships so many people went through to build our country. I loved it and can't wait to recommend it to other readers of historical fiction.